With Which Member of His Family Is Equiano Reunited

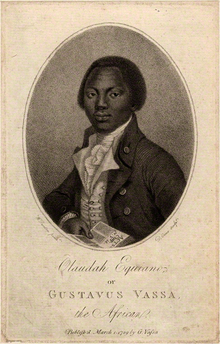

| Olaudah Equiano | |

|---|---|

Equiano past Daniel Orme, frontispiece of his autobiography (1789) | |

| Built-in | c. 1745 Eboe region of the Kingdom of Benin (today southern Nigeria)[1] [2] or, possibly, Southward Carolina, British North America[three] |

| Died | 31 March 1797 (aged 52) Westminster, Middlesex, Bang-up Great britain[4] |

| Other names | Gustavus Vassa, Jacob, Michael |

| Occupation |

|

| Known for | Influence over British abolitionists; his autobiography |

| Spouse(due south) | Susannah Cullen (m. 1792; died 1796) |

| Children | Anna Maria Vassa Joanna Vassa |

Olaudah Equiano (; c. 1745 – 31 March 1797), known for virtually of his life equally Gustavus Vassa (),[five] [six] was a author and abolitionist from, co-ordinate to his memoir, the Eboe (Igbo) region of the Kingdom of Benin (today southern Nigeria). Enslaved as a child in Africa, he was taken to the Caribbean and sold as a slave to a Royal Navy officer. He was sold twice more only purchased his freedom in 1766.

As a freedman in London, Equiano supported the British abolitionist movement. He was part of the Sons of Africa, an abolitionist group composed of Africans living in U.k., and he was active amongst leaders of the anti-slave trade movement in the 1780s. He published his autobiography, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano (1789), which depicted the horrors of slavery. It went through nine editions in his lifetime and helped gain passage of the British Slave Trade Act 1807, which abolished the slave trade.[7] Equiano married an English language adult female, Susannah Cullen, in 1792 and they had 2 daughters. He died in 1797 in Westminster.

Since the tardily 20th century, when his autobiography was published in a new edition, he has been increasingly studied past a range of scholars, including from his homeland.[1] [3]

Early life and enslavement [edit]

According to his memoir, Equiano was built-in in Essaka, Eboe, in the Kingdom of Benin around 1745.[viii] The hamlet was in the southeast part of present-twenty-four hour period Nigeria. In his autobiography he wrote "My father, besides many slaves, had a numerous family unit, of which 7 lived to grow up" and that he was the youngest son. He stated that his male parent was 1 of the elders or chiefs who saturday in sentence with other elders to decide what to do about disputes or crimes. He refers to men chosen the Oye-Eboe who brought goods like guns, gunpowder and stale fish. In return Equiano says "Sometimes indeed we sold slaves to them, but they were only prisoners of war, or such amid us as had been convicted of kidnapping, or infidelity, and another crimes, which we esteemed heinous." He proceeded, "When a trader wants slaves, he applies to a chief for them, and tempts him with his wares ... and accepts the price of his fellow animate being's freedom with every bit petty reluctance as the aware merchant". This was unremarkably the cause of war in order to obtain the slaves to appease 'his avarice'.[ix]

Equiano recounted an incident of an attempted kidnapping of children in his Igbo village, which was foiled by adults. When he was around the historic period of eleven, he and his sister were left lone to await later their family premises, equally was common when adults went out of the firm to work. They were both kidnapped and taken far from their hometown, separated and sold to slave traders. He tried to escape but was thwarted. After his owners changed several times, Equiano happened to meet with his sis but they were separated again. 6 or seven months afterwards he had been kidnapped, he arrived at the coast where he was taken on board a European slave ship.[10] [eleven] He was transported with 244 other enslaved Africans across the Atlantic Ocean to Barbados in the British West Indies. He and a few other slaves were sent on for sale in the Colony of Virginia.

Literary scholar Vincent Carretta argued in his 2005 biography of Equiano that the activist could have been born in colonial South Carolina rather than Africa, based on a 1759 parish baptismal record that lists Equiano'southward identify of birth as Carolina and a 1773 send'southward muster that indicates Due south Carolina.[3] [12] Carretta's conclusion is disputed by other scholars who believe the weight of evidence supports Equiano's business relationship of coming from Africa.[13]

In Virginia, Equiano was bought past Michael Henry Pascal, a lieutenant in the Royal Navy. Pascal renamed the boy "Gustavus Vassa", afterward the 16th-century Rex of Sweden Gustav Vasa[x] who began the Protestant Reformation in Sweden. Equiano had already been renamed twice: he was chosen Michael while on board the slave ship that brought him to the Americas; and Jacob, by his starting time owner. This fourth dimension, Equiano refused and told his new owner that he would prefer to be called Jacob. His refusal, he says, "gained me many a gage" and eventually he submitted to the new proper noun. : 62 He used this proper noun for the rest of his life, including on all official records; he only used Equiano in his autobiography.[5]

Pascal took Equiano with him when he returned to England and had him accompany him as a valet during the Vii Years' War with French republic (1756–1763). Equiano gives bystander reports of the Siege of Louisbourg (1758), the Battle of Lagos (1759) and the Capture of Belle Île (1761). Also trained in seamanship, Equiano was expected to assist the ship's crew in times of boxing; his duty was to booty gunpowder to the gun decks. Pascal favoured Equiano and sent him to his sister-in-law in Great United kingdom so that he could attend school and learn to read and write.

Equiano converted to Christianity and was baptised at St Margaret'south, Westminster, on ix February 1759, when he was described in the parish register every bit "a Black, built-in in Carolina, 12 years old".[14] His godparents were Mary Guerin and her brother, Maynard, who were cousins of his main Pascal. They had taken an interest in him and helped him to larn English language. Later, when Equiano's origins were questioned later his book was published, the Guerins testified to his lack of English when he get-go came to London.[5]

In December 1762, Pascal sold Equiano to Captain James Doran of the Charming Sally at Gravesend, from where he was transported back to the Caribbean, to Montserrat, in the Leeward Islands. There, he was sold to Robert King, an American Quaker merchant from Philadelphia who traded in the Caribbean.[fifteen]

Release [edit]

Robert Rex prepare Equiano to work on his shipping routes and in his stores. In 1765, when Equiano was about 20 years onetime, King promised that for his purchase price of forty pounds (equivalent to £five,600 in 2020) he could buy his liberty.[16] Rex taught him to read and write more fluently, guided him along the path of organized religion, and allowed Equiano to appoint in profitable trading for his ain business relationship, as well as on his owner's behalf. Equiano sold fruits, glass tumblers and other items betwixt Georgia and the Caribbean islands. Male monarch allowed Equiano to buy his freedom, which he achieved in 1766. The merchant urged Equiano to stay on as a business concern partner. Even so, Equiano found information technology dangerous and limiting to remain in the British colonies as a freedman. While loading a ship in Georgia, he was almost kidnapped back into enslavement.

Liberty [edit]

Past about 1768, Equiano had gone to England. He continued to piece of work at sea, travelling sometimes as a deckhand based in England. In 1773 on the Royal Navy ship HMS Racehorse, he travelled to the Chill in an expedition towards the Northward Pole.[17] On that voyage he worked with Dr Charles Irving, who had adult a process to dribble seawater and later made a fortune from it. Ii years later, Irving recruited Equiano for a project on the Mosquito Declension in Fundamental America, where he was to employ his African background to help select slaves and manage them as labourers on sugar-cane plantations. Irving and Equiano had a working relationship and friendship for more than a decade, but the plantation venture failed.[eighteen]

Equiano left the Musquito Coast in 1776 and arrived at Plymouth, England, on 7 January 1777.[ citation needed ]

Pioneer of the abolitionist crusade [edit]

Equiano settled in London, where in the 1780s he became involved in the abolitionist move. The motion to cease the slave trade had been specially strong among Quakers, merely the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade was founded in 1787 as a not-denominational grouping, with Anglican members, in an attempt to influence parliament directly. Under the Test Human action, just those prepared to receive the sacrament of the Lord's Supper according to the rites of the Church building of England were permitted to serve as MPs. Equiano had been influenced by George Whitefield's evangelism.

As early as 1783, Equiano informed abolitionists such as Granville Sharp almost the slave trade; that year he was the get-go to tell Sharp nearly the Zong massacre, which was being tried in London as litigation for insurance claims. It became a crusade célèbre for the abolitionist motion and contributed to its growth.[nineteen]

On 21 Oct 1785 he was one of eight delegates from Africans in America to present an 'Address of Thanks' to the Quakers at a meeting in Gracechurch Street, London. The accost referred to A Caution to United kingdom and her Colonies by Anthony Benezet, founder of the Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Chains.[20]

Equiano was befriended and supported by abolitionists, many of whom encouraged him to write and publish his life story. He was supported financially in this effort by philanthropic abolitionists and religious benefactors. His lectures and preparation for the volume were promoted past, among others, Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon.

Memoir [edit]

Plaque at Riding Firm Street, Westminster, noting the place where Equiano lived and published his narrative

Entitled The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African (1789), the book went through nine editions in his lifetime. It is 1 of the earliest-known examples of published writing past an African writer to be widely read in England. By 1792, it was a best seller and had been published in Russia, Germany, Holland and the United States. It was the first influential slave narrative of what became a large literary genre. Just Equiano's experience in slavery was quite dissimilar from that of about slaves; he did not participate in field work, he served his owners personally and went to body of water, was taught to read and write, and worked in trading.[19]

Equiano'south personal account of slavery, his journeying of advocacy, and his experiences equally a black immigrant acquired a sensation on publication. The volume fuelled a growing anti-slavery move in Peachy Uk, Europe and the New World.[21] His account surprised many with the quality of its imagery, description and literary style.

In his account, Equiano gives details about his hometown and the laws and customs of the Eboe people. Later being captured equally a boy, he described communities he passed through every bit a captive on his way to the coast. His biography details his voyage on a slave ship and the brutality of slavery in the colonies of the West Indies, Virginia and Georgia.

Equiano commented on the reduced rights that freed people of color had in these same places, and they also faced risks of kidnapping and enslavement. Equiano embraced Christianity at the age of 14 and its importance to him is a recurring theme in his autobiography. He was baptised into the Church building of England in 1759; he described himself in his autobiography as a "protestant of the church building of England" but also flirted with Methodism.[22]

Several events in Equiano'due south life led him to question his religion. He was distressed in 1774 by the kidnapping of his friend, a black cook named John Annis, who was taken forcibly off the British send Anglicania on which they were both serving.[ citation needed ] His friend'southward kidnapper, William Kirkpatrick, did not abide by the decision in the Somersett Case (1772), that slaves could not be taken from England without their permission, as mutual law did not support the institution in England & Wales. Kirkpatrick had Annis transported to Saint Kitts, where he was punished severely[ why? ] and worked as a plantation labourer until he died. With the aid of Granville Precipitous, Equiano tried to get Annis released earlier he was shipped from England but was unsuccessful. He heard that Annis was not costless from suffering until he died in slavery.[23] Despite his questioning, he affirms his religion in Christianity, equally seen in the penultimate sentence of his piece of work that quotes the prophet Micah (Micah 6:8): "After all, what makes whatsoever outcome important, unless past its ascertainment we become better and wiser, and learn 'to do justly, to dearest mercy, and to walk humbly earlier God?'"

In his account, Equiano also told of his settling in London. He married an English woman and lived with her in Soham, Cambridgeshire, where they had two daughters. He became a leading abolitionist in the 1780s, lecturing in numerous cities confronting the slave trade. Equiano records his and Granville Abrupt'due south central roles in the anti-slave trade movement, and their effort to publicise the Zong massacre, which became known in 1783.

Reviewers have constitute that his book demonstrated the full and complex humanity of Africans as much equally the inhumanity of slavery. The volume was considered an exemplary work of English language literature past a new African author. Equiano did so well in sales that he achieved independence from his benefactors. He travelled throughout England, Scotland and Ireland promoting the book. He worked to better economic, social and educational conditions in Africa. Specifically, he became involved in working in Sierra Leone, a colony founded in 1792 for freed slaves by Britain in West Africa.

Later years [edit]

During the American Revolutionary War, Britain had recruited black people to fight with it by offering freedom to those who left rebel masters. In practice, it also freed women and children, and attracted thousands of slaves to its lines in New York City, which it occupied, and in the Due south, where its troops occupied Charleston, South Carolina. When British troops were evacuated at the stop of the war, their officers also evacuated these American slaves. They were resettled in the Caribbean, in Nova Scotia, in Sierra Leone in Africa, and in London. Britain refused to return the slaves, which the U.s. sought in peace negotiations.

In 1783, following the United states' gaining independence, Equiano became involved in helping the Black Poor of London, who were mostly those African-American slaves freed during and after the American Revolution by the British. There were also some freed slaves from the Caribbean, and some who had been brought past their owners to England and freed later after the decision that Britain had no footing in mutual police force for slavery. The black customs numbered about twenty,000.[24] After the Revolution some iii,000 quondam slaves had been transported from New York to Nova Scotia, where they became known as Black Loyalists, among other Loyalists besides resettled there. Many of the freedmen institute it difficult to make new lives in London or Canada.

Equiano was appointed "Commissary of Provisions and Stores for the Black Poor going to Sierra Leone" in November 1786.[ citation needed ] This was an expedition to resettle London's Black Poor in Freetown, a new British colony founded on the west coast of Africa, in present-day Sierra Leone. The blacks from London were joined by more than than 1,200 Black Loyalists who chose to leave Nova Scotia. They were aided by John Clarkson, younger brother of abolitionist Thomas Clarkson. Jamaican maroons, as well as slaves liberated from illegal slave-trading ships subsequently Britain abolished the slave trade, likewise settled at Freetown in the early decades. Equiano was dismissed from the new settlement after protesting confronting financial mismanagement and he returned to London.[25] [26]

Equiano was a prominent effigy in London and ofttimes served as a spokesman for the black community. He was one of the leading members of the Sons of Africa, a pocket-sized abolitionist group equanimous of free Africans in London. They were closely allied with the Club for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. Equiano'southward comments on problems were published in newspapers such equally the Public Advertiser and the Morn Chronicle. He replied to James Tobin in 1788, in the Public Advertiser, attacking two of his pamphlets and a related book from 1786 by Gordon Turnbull.[27] [28] Equiano had more than of a public phonation than most Africans or Blackness Loyalists and he seized various opportunities to employ it.[29]

Equiano was an active member of the radical working-class London Corresponding Society, which campaigned to extend the vote to working men. In 1792 he lodged with the order's founder Thomas Hardy. At this time, due to the excesses of the French Revolution, British order was tense because of fears of revolution. Reformers were considered more than suspect than in other periods. In the 1794 Treason Trials, Thomas Hardy, John Horne Tooke and John Thelwall were tried for high treason just acquitted.

Marriage and family [edit]

On 7 April 1792, Equiano married Susannah Cullen, a local woman, in St Andrew's Church, Soham, Cambridgeshire.[33] The original spousal relationship register containing the entry for Vassa and Cullen is held today past the Cambridgeshire Archives and Local Studies. He included his marriage in every edition of his autobiography from 1792 onwards. The couple settled in the expanse and had two daughters, Anna Maria (1793–1797) and Joanna (1795–1857) who were baptised at Soham church.

Susannah died in February 1796, aged 34, and Equiano died a year afterwards that on 31 March 1797.[10] Soon subsequently, the elder daughter died at the age of four, leaving the younger child, Joanna Vassa, to inherit Equiano'southward manor when she was 21; it was and then valued at £950 (equivalent to £74,000 in 2020). Anna Maria is commemorated by a plaque at St Andrew'due south Church, Chesterton, Cambridge.[34] Joanna Vassa married the Reverend Henry Bromley, a Congregationalist minister, in 1821. They are both cached at the not-denominational Abney Park Cemetery in Stoke Newington, London; the Bromleys' monument is at present a Grade II listed building.[35]

Last days and will [edit]

He drew up his volition on 28 May 1796. At the time he made this will he was living at the Plaisterers' Hall,[36] and so on Addle Street, in Aldermanbury in the City of London.[37] [38] He moved to John Street (at present Whitfield Street), close to Whitefield's Tabernacle, Tottenham Court Route. At his death on 31 March 1797, he was living in Paddington Street, Westminster.[4] Equiano's death was reported in American[39] as well every bit British newspapers.

Equiano was buried at Whitefield's Tabernacle on 6 April. The entry in the register reads "Gustus Vasa, 52 years, Southt Mary Le bone".[xl] [41] His burying place has been lost. The small burial footing lay either side of the chapel and is now Whitfield Gardens.[42] The site of the chapel is now the American International Church.

Equiano's will, in the outcome of his daughters' deaths before reaching the age of 21, bequeathed one-half his wealth to the Sierra Leone Visitor for a schoolhouse in Sierra Leone, and half to the London Missionary Society.[38]

[edit]

Following publication in 1967 of a newly edited version of his memoir past Paul Edwards, involvement in Equiano revived. Scholars from Nigeria have besides begun studying him. He was valued equally a pioneer in asserting "the dignity of African life in the white club of his fourth dimension".[43]

In researching his life, some scholars since the late 20th century take disputed Equiano's account of his origins. In 1999, Vincent Carretta, a professor of English editing a new version of Equiano's memoir, found two records that led him to question the onetime slave's account of being born in Africa. He starting time published his findings in the journal Slavery and Abolitionism.[12] [44] At a 2003 briefing in England, Carretta defended himself against Nigerian academics, like Obiwu, who defendant him of "pseudo-detective work" and indulging "in vast publicity gamesmanship".[45] In his 2005 biography, Carretta suggested that Equiano may have been born in South Carolina rather than Africa, as he was twice recorded from there. Carretta wrote:

Equiano was certainly African past descent. The circumstantial testify that Equiano was also African-American past nascency and African-British by pick is compelling but not absolutely conclusive. Although the circumstantial evidence is not equivalent to proof, anyone dealing with Equiano's life and art must consider it.[3]

According to Carretta, Equiano/Vassa'due south baptismal tape and a naval muster roll document him as from South Carolina.[12] Carretta interpreted these anomalies as possible evidence that Equiano had fabricated up the account of his African origins, and adopted cloth from others. But Paul Lovejoy, Alexander X. Byrd and Douglas Chambers note how many general and specific details Carretta can document from sources that related to the slave trade in the 1750s as described by Equiano, including the voyages from Africa to Virginia, auction to Pascal in 1754, and others. They conclude he was more likely telling what he understood as fact, rather than creating a fictional account; his work is shaped as an autobiography.[17] [19] [46]

Lovejoy wrote that:

coexisting bear witness indicates that he was born where he said he was, and that, in fact, The Interesting Narrative is reasonably accurate in its details, although, of course, subject to the aforementioned criticisms of selectivity and self-interested distortion that characterize the genre of autobiography.

Lovejoy uses the proper noun of Vassa in his commodity, since that was what the man used throughout his life, in "his baptism, his naval records, spousal relationship certificate and will".[xix] He emphasises that Vassa only used his African proper noun in his autobiography.

Other historians too argue that the fact that many parts of Equiano's account can be proven lends weight to accepting his account of African nascency. Equally historian Adam Hochschild has written:

In the long and fascinating history of autobiographies that distort or exaggerate the truth. ... Seldom is one crucial portion of a memoir totally fabricated and the remainder scrupulously accurate; among autobiographers ... both dissemblers and truth-tellers tend to be consequent.[47]

He also noted that "since the 'rediscovery' of Vassa's account in the 1960s, scholars have valued information technology equally the well-nigh all-encompassing account of an eighteenth-century slave's life and the hard passage from slavery to freedom".[19]

Legacy [edit]

- The Equiano Society was formed in London in Nov 1996. Its master objective is to publicise and gloat the life and work of Olaudah Equiano.[48] [49]

- In 1789 Equiano moved to ten Union Street (at present 73 Riding House Street). A City of Westminster commemorative green plaque was unveiled there on eleven October 2000 as part of Black History Month. Educatee musicians from Trinity Higher of Music played a fanfare composed by Professor Ian Hall for the unveiling.[50]

- Equiano is honoured in the Church of England and remembered in its Agenda of saints on 30 July, along with Thomas Clarkson and William Wilberforce who worked for abolition of the slave trade and slavery.[51]

- In 2007, the year of the celebration in Britain of the bicentenary of the abolition of the slave trade, Equiano's life and achievements were included in the National Curriculum, together with William Wilberforce. In December 2012 The Daily Mail claimed that both would exist dropped from the curriculum, a merits which itself became subject to controversy.[52] In January 2013 Performance Black Vote launched a petition to request Didactics Secretary Michael Gove to keep both Equiano and Mary Seacole in the National Curriculum.[53] American Rev. Jesse Jackson and others wrote a letter to The Times protesting against the mooted removal of both figures from the National Curriculum.[54] [55]

- A statue of Equiano, made by pupils of Edmund Waller Schoolhouse, was erected in Telegraph Loma Lower Park, New Cantankerous, London, in 2008.[56]

- The caput of Equiano is included in Martin Bond's 1997 sculpture Wall of the Ancestors in Deptford, London

- U.S. author Ann Cameron adapted Equiano'due south autobiography for children, leaving almost of the text in Equiano'due south own words; the book was published in 1995 in the U.S. by Random House every bit The Kidnapped Prince: The Life of Olaudah Equiano, with an introduction by historian Henry Louis Gates Jr.

- On sixteen Oct 2017, Google Putter honoured Equiano by celebrating the 272nd year since his birth.[57]

- A crater on Mercury was named "Equiano" in 1976.[58]

- In 2019, Google Deject named a subsea cable running from Portugal through the Westward Coast of Africa and terminating in South Africa subsequently Equiano.[59]

- Olaudah Equiano is remembered (with William Wilberforce and Thomas Clarkson) in the Church of England with a Lesser Festival on 30 July.[lx]

Representation in other media [edit]

- A 28-minute documentary, Son of Africa: The Slave Narrative of Olaudah Equiano (1996), produced by the BBC and directed by Alrick Riley, uses dramatic reconstruction, archival material and interviews to provide the social and economic context for his life and the slave merchandise.[61]

Numerous works near Equiano have been produced for and since the 2007 bicentenary of Britain's abolitionism of the slave trade:

- Equiano was portrayed past the Senegalese musician Youssou Northward'Dour in the film Amazing Grace (2006).

- African Snowfall (2007), a play by Murray Watts, takes place in the mind of John Newton, a captain in the slave trade who later became an Anglican cleric and hymnwriter. It was outset produced at the York Theatre Majestic every bit a co-product with Riding Lights Theatre Visitor, transferring to the Trafalgar Studios in London's West End and a national tour. Newton was played by Roger Alborough and Equiano by Israel Oyelumade.

- Kent historian Dr Robert Hume wrote a children's book entitled Equiano: The Slave with the Loud Voice (2007), illustrated by Cheryl Ives.[62]

- David and Jessica Oyelowo appeared as Olaudah and his wife in Grace Unshackled – The Olaudah Equiano Story (2007), a BBC 7 radio accommodation of Equiano'south autobiography.[63]

- The British jazz creative person Soweto Kinch's start anthology, Conversations with the Unseen (2003), contains a track entitled "Equiano's Tears".

- Equiano was portrayed by Jeffery Kissoon in Margaret Busby's 2007 play An African Cargo, staged at the Greenwich Theatre.[64]

- Equiano is portrayed past Danny Sapani in the BBC series Garrow's Law (2010).

- The Nigerian writer Chika Unigwe has written a fictional memoir of Equiano: The Blackness Messiah, originally published in Dutch: De zwarte messias (2013).[65]

- In Jason Immature's 2007 brusque animated motion-picture show, The Interesting Narrative of Olaudah Equiano, Chris Rochester portrayed Equiano.[66]

- A TikTok serial under the account @equiano.stories recounts "the true story of Olaudah Equiano", a drove of episodes reimagining the childhood of Equiano. The story is captured every bit a self-recorded, first-person account, inside the format of Instagram Stories/TikTok posts, using video, still images, and text.[67]

See likewise [edit]

- Black British elite, the form that Equiano belonged to

- Ottobah Cugoano, an African abolitionist active in Britain in the tardily 18th century

- Phillis Wheatley, recognised in the 18th century every bit the first African-American poet; first African-American woman to publish a book

- List of slaves

- List of civil rights leaders

Notes [edit]

References [edit]

- ^ a b F. Onyeoziri (2008),"Olaudah Equiano: Facts well-nigh his People and Place of Nascency" Archived 17 October 2022 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ A. Alabi (2005). Telling Our Stories: Continuities and Divergences in Black Autobiographies. Springer. p. 54. ISBN978-1403980946. Archived from the original on 17 October 2017.

- ^ a b c d Carretta, Vincent (2005). Equiano, the African: Biography of a Cocky-Made Man . University of Georgia Press. p. xvi. ISBN978-0-8203-2571-2.

- ^ a b Vincent Carretta, Equiano, the African: Biography of a Self-made Man, University of Georgia Press, 2005, p. 365.

- ^ a b c Lovejoy, Paul East. (2006). "Autobiography and Retentivity: Gustavus Vassa, alias Olaudah Equiano, the African". Slavery & Abolition. 27 (3): 317–347. doi:10.1080/01440390601014302. S2CID 146143041.

- ^ Christer Petley, White Fury: A Jamaican Slaveholder and the Age of Revolution (Oxford: Oxford Academy Press, 2018), p. 151.

- ^ Equiano, Olaudah (1999). The Life of Olaudah Equiano, or, Gustavus Vassa, the African. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. ISBN978-0-486-40661-9.

- ^ "The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African". p. 3. Retrieved 1 April 2022. "I was born, in the year 1745, situated in a mannerly fruitful vale, named Essaka."}}

- ^ Quotations from Brooks, J., (ed.), The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, The African. Written by Himself, R.R. Donnelly & Sons Company, 2004, Capacity I and Two.

- ^ a b c "Olaudah Equiano". BBC History. Archived from the original on 13 July 2006. Retrieved five July 2006.

- ^ Equiano, Olaudah (2005). The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano.

- ^ a b c Robin Blackburn, "The True Story of Equiano", The Nation, 2 November 2005 (archived). Retrieved 28 September 2014 (subscription required)

- ^ Bugg, John (October 2006). "The Other Interesting Narrative: Olaudah Equiano's Public Book Tour". PMLA. 121 (5): 1424–1442, esp. 1425. doi:x.1632/pmla.2006.121.5.1424. JSTOR 25501614. S2CID 162237773.

- ^ David Dabydeen, "Equiano the African: Biography of a Self-made Man past Vincent Carretta" (book review), The Guardian, 3 December 2005, Archived fourteen November 2022 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- ^ Equiano, Olaudah (1790). The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, Or Gustavus Vassa, The African.

- ^ Walvin, James (2000). An African'due south Life: The Life and Times of Olaudah Equiano, 1745–1797. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 71. ISBN978-0-8264-4704-three.

- ^ a b Douglas Chambers, "'Near an Englishman': Carretta's Equiano" Archived 8 October 2022 at the Wayback Car, H-Net Reviews, November 2007. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ Lovejoy (2006), p. 332.

- ^ a b c d due east Paul East. Lovejoy, "Autobiography and Memory: Gustavus Vassa, allonym Olaudah Equiano, the African" Archived 4 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Slavery and Abolitionism 27, no. 3 (2006): 317–347.

- ^ "Chelmsford". Chelmsford Relate. 5 May 1786. p. 3.

- ^ Kamille Stone Stanton and Julie A. Chappell (eds), Transatlantic Literature in the Long Eighteenth Century, Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars, 2011.

- ^ Hinds, Elizabeth Jane Wall (Winter 1998). "The Spirit of Trade: Olaudah Equiano's Conversion, Legalism, and the Merchant'due south Life". The African American Review. 32 (4): 635–647. doi:10.2307/2901242. JSTOR 2901242.

- ^ "Excerpt from Chap. 10, An Interesting Narrative". Archived from the original on 2 Feb 2014. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- ^ Lovejoy (2006), p. 334.

- ^ David Damrosch, Susan J. Wolfson, Peter J. Manning (eds), The Longman Anthology of British Literature, Volume 2A: The Romantics and Their Contemporaries (2003), p. 211.

- ^ Michael Siva, Why did Black Londoners not join the Sierra Leone Resettlement Scheme 1783–1815? (London: Open Academy, 2014), pp. 28–33.

- ^ Vincent Carretta; Philip Gould (5 Feb 2015). Genius in Bondage: Literature of the Early on Black Atlantic. University Press of Kentucky. p. 67. ISBN978-0-8131-5946-i.

- ^ Peter Fryer (1984). Staying Power: The History of Black People in Britain. Academy of Alberta. pp. 108–ix. ISBN978-0-86104-749-ix.

- ^ Shyllon, Folarin (September 1977). "Olaudah Equiano; Nigerian Abolitionist and Starting time Leader of Africans in Britain". Journal of African Studies. 4 (iv): 433–451.

- ^ "Trading faces". BBC.

- ^ "Portrait of an African (probably Ignatius Sancho, 1729–1780)". artuk.org.

- ^ "The Equiano Portraits". world wide web.brycchancarey.com. Archived from the original on 1 February 2017. Retrieved eighteen May 2017.

- ^ "Olaudah Equiano or Gustavus Vassa The African - 200th Ceremony of the Abolition of Slavery". www.equiano.soham.org.uk . Retrieved fourteen Baronial 2021.

- ^ Celebrated England, "Church of St Andrew, Cambridge (1112541)", National Heritage List for England , retrieved 20 October 2020

- ^ Celebrated England, "Monument to Joanna Vassa in Abney Park Cemetery (1392851)", National Heritage List for England , retrieved xviii Jan 2020

- ^ Bamping, Nigel (17 July 2020). "The Plaisterers and the abolition of slavery". Plaistererslivery.co.u.k. . Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ^ "Volition of Gustavus Vassa or Olaudah Equiano, Gentleman of Addle Street Aldermanbury , City of London." England & Wales, Prerogative Courtroom of Canterbury Wills, 1384-1858, PROB eleven: Will Registers: 1796 - 1798, Slice 1289: Exeter Quire Numbers 238 - 284. The National Athenaeum, Kew. Retrieved 14 Nov 2020.

- ^ a b "Transcript Gustavus Vassa Provides for His Family PROB ten/3372". Nationalarchives.gov.united kingdom/. TNA. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ^ "DEATHS: In London, Mr. Gustavus Vassa, the African, well known to the public for the interesting narrative of his life." Weekly Oracle (New London, CT), 12 August 1797, p. 3.

- ^ "{title}". 16 October 2017. Archived from the original on 23 October 2017. Retrieved 23 Oct 2017.

- ^ London Metropolitan Archives; Clerkenwell, London, England; Whitefield'southward Memorial Church building [Formerly Tottenham Court Route Chapel], Tottenham Court Road, Saint Pancras, Register of burials; Reference Code: LMA/4472/A/01/004

- ^ "Whitfield Gardens". Londongardensonline.org.u.k. . Retrieved 21 Jan 2020. [ permanent expressionless link ]

- ^ O. S. Ogede, "'The Igbo Roots of Olaudah Equiano' by Catherine Acholonu" Archived 23 June 2022 at the Wayback Motorcar, Africa: Periodical of the International African Constitute, Vol. 61, No. 1, 1991, at JSTOR (subscription required)

- ^ Vincent Carretta, "Olaudah Equiano or Gustavus Vassa? New Light on an Eighteenth-Century Question of Identity", Slavery and Abolition xx, no. 3 (1999): 96–105.

- ^ "Slave fiction?". Florida International Academy. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ^ Alexander X. Byrd, "Eboe, Country, Nation, and Gustavus Vassa'south Interesting Narrative" Archived 5 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine, William and Mary Quarterly 63, no. one (2006): 123–148, at JSTOR (subscription required)

- ^ Hochschild, Adam (2006). Bury the Bondage: Prophets and Rebels in the Fight to Gratuitous an Empire'south Slaves. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 372. ISBN978-0-618-61907-8.

- ^ "The Equiano Society: Data and Forthcoming Events". www.brycchancarey.com. Archived from the original on 22 April 2012. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- ^ Thomas, Shirley (10 February 2019). "Iconic Guyanese working to promote Caribbean heritage in Uk". Guyana Chronicle . Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ "Metropolis of Westminster greenish plaques". Archived from the original on sixteen July 2012.

- ^ "William Wilberforce, Olaudah Equiano and Thomas Clarkson" Archived 9 October 2022 at the Wayback Car, Common Worship Texts: Festivals. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ "Here'due south why Mary Seacole and other inspiring black figures should stay". 8 February 2013.

- ^ "OBV initiate Mary Seacole Petition". Operation Black Vote (OBV). 3 January 2013. Archived from the original on ix January 2013. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ^ Hurst, Greg (9 Jan 2013). "Civil rights veteran Jesse Jackson joins fight against curriculum changes". The Times.

- ^ "Open letter to Rt Michael Gove MP". Operation Black Vote (OBV). nine Jan 2013. Archived from the original on 14 January 2013. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ^ "Little treasures: #1 Equiano". 25 June 2008. Retrieved vii May 2019.

- ^ "Olaudah Equiano's 272nd Altogether". Google. Archived from the original on 16 October 2017. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ^ WGPSN

- ^ "Introducing Equiano, a subsea cable from Portugal to Southward Africa". Google Cloud . Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ^ "The Calendar". The Church of England . Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Son of Africa: The Slave Narrative of Olaudah Equiano Archived 1 October 2006 at the Wayback Auto, 1996, sale at California Newsreel.

- ^ Robert Hume (2007), Equiano: The Slave with the Loud Vocalism, Stone Publishing House, ISBN 978-0-9549909-1-6.

- ^ "Grace Unshackled: The Olaudah Equiano Story". BBC. 15 April 2007. Archived from the original on ii February 2009. Retrieved 15 January 2009.

- ^ "An African Cargo, 2007" Archived eighteen April 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Nitro Music Theatre.

- ^ Chika Unigwe (2013), De zwarte messias, De Bezige Bij, ISBN 978-90-8542-454-3

- ^ The Interesting Narrative of Olaudah Equiano at IMDb

- ^ "The true story of Olaudah Equiano". A articulation characteristic film project by Stelo Stories Studio and the DuSable Museum of African American History. Early on 2022.

Further reading [edit]

- The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African at Wikisource.

- For the history of the Narrative'southward publication, run across James Green, "The Publishing History of Olaudah Equiano'southward Interesting Narrative", Slavery and Abolition xvi, no. 3 (1995): 362–375.

- Due south. E. Ogude, "Facts into fiction: Equiano's narrative reconsidered", Inquiry into African Literatures, Vol. 13, No. 1, 1982

- South. E. Ogude, "Olaudah Equiano and the tradition of Defoe", African Literature Today, Vol. 14, 1984

- James Walvin, An African'due south Life: The Life and Times of Olaudah Equiano, 1745–1797 (London: Continuum, 1998)

- Luke Walker, Olaudah Equiano: The Interesting Human being (Wrath and Grace Publishing, 2017)

External links [edit]

- Works past Olaudah Equiano in eBook grade at Standard Ebooks

- Works by Olaudah Equiano at Projection Gutenberg

- Works by or about Olaudah Equiano at Internet Archive

- Works by Olaudah Equiano at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Frederick Quinn, "Olaudah Equiano", Dictionary of African Christian Biography, article reproduced with permission from African Saints: Saints, Martyrs, and Holy People from the Continent of Africa, copyright © 2002 by Frederick Quinn, New York: Crossroads Publishing Company

- Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African, Brycchan Carey website, Carey 2003–2005. Includes Carey'due south comprehensive drove of resources for the study of Equiano. The Nativity section [i] includes a detailed comparing of differing data related to his place of birth.

- The Equiano Project Archived 23 Oct 2022 at the Wayback Machine, The Equiano Society and Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery

- Office I: "Olaudah Equiano", Africans in America, PBS

- "Historic figures: Olaudah Equiano", BBC

- "Remembering Equiano in Soham", Remembering Equiano in Soham, Cambridgeshire

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Olaudah_Equiano

0 Response to "With Which Member of His Family Is Equiano Reunited"

Postar um comentário